Oral hygiene may be a key factor in diabetes risk, new data from a Korean national health database suggest.

"Frequent toothbrushing may be an attenuating factor for the risk of new-onset diabetes, and the presence of periodontal disease and increased number of missing teeth may be augmenting factors," write Yoonkyung Chang, MD, of the Department of Neurology, Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues.

"Improving oral hygiene may be associated with a decreased risk of occurrence of new-onset diabetes," they continue in an article published online March 2 in Diabetologia.

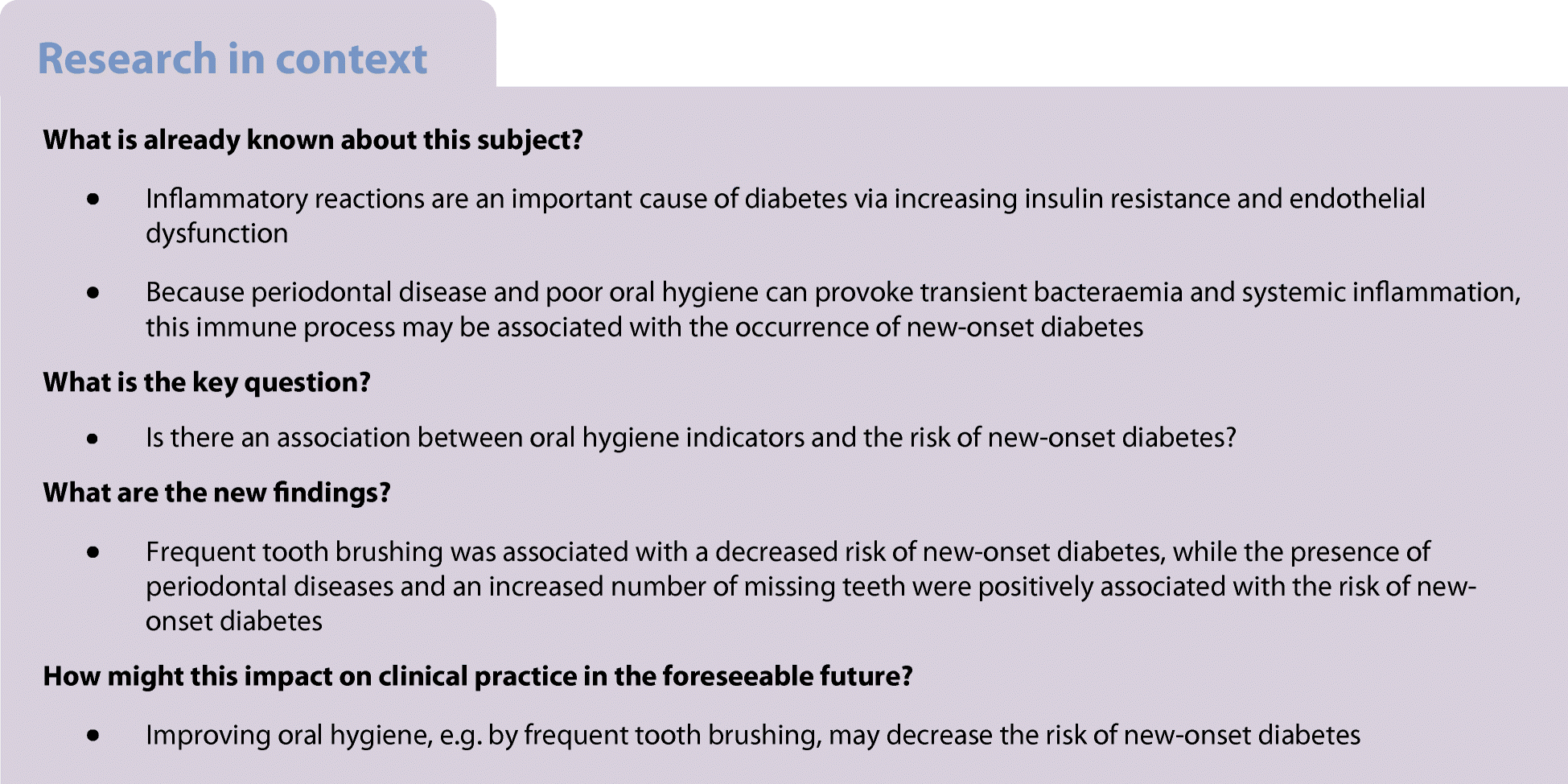

Periodontal disease involves inflammatory reactions affecting the surrounding tissues of the teeth. Inflammation, in turn, is an important cause of diabetes via increasing insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, Chang and colleagues explain.

They analyzed data from 188,013 individuals from the Korean National Health Insurance System – Health Screening Cohort who had complete data and did not have diabetes at baseline (2003-2006). Oral hygiene behaviors, including frequency of toothbrushing, and dental visits or cleanings, were collected by self-report.

Over a median follow-up of 10 years, there were 31,545 new cases of diabetes, with an estimated overall 10-year event rate of 16.1%. The rate was 17.2% for those with periodontal disease at baseline versus 15.8% for those without, which was a significant difference even after adjustments for multiple confounders (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; P < .001).

Compared with no missing teeth, the event rate for new-onset diabetes rose from 15.4% for one missing tooth (HR, 1.08; P < .001) to 21.4% for 15 or more missing teeth (HR, 1.21; P < .001).

Professional dental cleaning did not have a significant effect after multivariate analysis.

However, the number of daily tooth-brushings by the individual did. Compared with 0-1 times/day, those who brushed ≥ 3 times/day had a significantly lower risk for new-onset diabetes (HR, 0.92; P < .001).

In subgroup analyses, periodontal disease was more strongly associated with new-onset diabetes among adults aged 51 and younger (HR, 1.14) compared with those aged 52 and older (HR, 1.06).

The study was supported by a grant from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

Diabetologia. Published online March 2, 2020. Abstract and full text free pdf

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00125-020-05112-9

Improved oral hygiene is associated with decreased risk of new-onset diabetes: a nationwide population-based cohort study

Diabetologia (2020)Cite this article

- 142 Accesses

- 134 Altmetric

- Metrics details

Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Inflammation plays an important role in the development of diabetes, a major global health problem. Periodontal disease is also common in the general population. Because periodontal disease and poor oral hygiene can provoke transient bacteraemia and systemic inflammation, we hypothesised that periodontal disease and oral hygiene indicators would be associated with the occurrence of new-onset diabetes.

Methods

In this study we analysed data collected between 2003 and 2006 on 188,013 subjects from the National Health Insurance System-Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea who had no missing data for demographics, past medical history, oral hygiene indicators or laboratory findings. The presence of periodontal disease was defined on the basis of a modified version of ICD-10 codes (Korean Classification of Disease, sixth edition), if claims for treatment for acute periodontitis (K052), chronic periodontitis (K053) and periodontosis (K054) were made more than two times by a dentist, or if, according to medical records, subjects received treatment by a dentist for periodontal disease with ICD-10 codes K052, K053 or K054. Oral hygiene behaviours (number of tooth brushings, a dental visit for any reason and professional dental cleaning) were collected as self-reported data of dental health check-ups. Number of missing teeth was ascertained by dentists during oral health examination. The incidence of new-onset diabetes was defined according to ICD-10 codes E10–E14. The criterial included at least one claim per year for both visiting an outpatient clinic and admission accompanying prescription records for any glucose-lowering agent, or was based on a fasting plasma glucose ≥7 mmol/l from NHIS-HEALS.

Results

Of the included subjects, 17.5% had periodontal disease. After a median follow-up of 10.0 years, diabetes developed in 31,545 (event rate: 16.1%, 95% CI 15.9%, 16.3%) subjects. In multivariable models, after adjusting for demographics, regular exercise, alcohol consumption, smoking status, vascular risk factors, history of malignancy and laboratory findings, the presence of periodontal disease (HR 1.09, 95% CI 1.07, 1.12, p < 0.001) and number of missing teeth (≥15 teeth) remained positively associated with occurrence of new-onset diabetes (HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.09, 1.33, p < 0.001, p for trend <0.001). Frequent tooth brushing (≥3 times/day) was negatively associated with occurrence of new-onset diabetes (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.89, 0.95, p < 0.001, p for trend <0.001).

Conclusions/interpretation

Frequent tooth brushing may be an attenuating factor and the presence of periodontal disease and an increased number of missing teeth may be augmenting factors for the occurrence of new-onset diabetes. Improving oral hygiene may be associated with a decreased risk of occurrence of new-onset diabetes.

From the article

Introduction

Over the last century, diabetes has become one of the largest global health emergencies in both Eastern and Western countries [1, 2]. Besides the well-known microvascular complications of diabetes, such as nephropathy, neuropathy and retinopathy, there is an expanding epidemic of macrovascular complications, including diseases of the carotid, cerebral, coronary and peripheral arteries [3]. Currently, several preventive strategies for new-onset diabetes have been suggested that include controlling factors related to a healthy lifestyle, such as maintaining proper weight and waist circumference, increasing regular exercise or physical activity, practising healthy dietary habits and undergoing regular physical examinations for identifying risk factors [4]. However, disease-modifying drugs and preventive methods for occurrence of new-onset diabetes are still lacking.

Periodontal disease is one of the most common diseases in the general population [5], involving a set of inflammatory reactions affecting the surrounding tissues of the teeth, such as the gingiva, periodontal ligaments and alveolar bone, which may ultimately cause tooth loss and elicit systemic inflammation [6]. In addition to periodontal disease, there are also indicators, such as frequency of tooth brushing, frequency of professional dental cleaning and number of missing teeth, that are closely related to oral hygiene [7,8,9]. Periodontal disease and poor oral hygiene indicators are associated with cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction and long-term mortality [10, 11].

Discussion

The key findings of our study are that frequency of tooth brushing was associated with a decreased risk of new-onset diabetes, and the presence of periodontal disease and missing teeth (≥15) may augment the risk of new-onset diabetes. In a previous case−control study in Japan, a lower frequency of tooth brushing was associated with a higher odds ratio (OR 1.61) of diabetes [26]. Among youths with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, acceptable diabetes control based on HbA1c was associated with tooth brushing (≥1 time daily: OR 3.10, 95% CI 1.26, 7.62) [27]. In terms of periodontal diseases and number of missing teeth, individuals with poorly controlled diabetes (HbA1c >9.0%) have been reported to have severe periodontal disease more frequently than those without diabetes (OR 2.90, 95% CI 1.40, 6.03) [28]. Moreover, more severe periodontal disease was associated with the development of glucose intolerance in non-diabetic individuals [29]. A US study reported that adults with diabetes had about twice the number of teeth missing as individuals without diabetes, and one in every five cases of edentulism was related to diabetes [30]. Our results are in concordance with these previous studies and provide additional information on the link between oral hygiene and new-onset diabetes in a longitudinal study in a general population setting.

Nevertheless, in our study the hazard ratios for the development of new-onset diabetes based on the presence of periodontal diseases and number of missing teeth were relatively low compared with those found in previous studies [31]. Similar to our results, in a previous study that defined periodontal disease by ICD-9 code, individuals with new-onset diabetes had a 1.04 times higher risk for periodontal disease compared with individuals without new-onset diabetes [32]. In contrast, in a National/European Health Interview Surveys study, the adjusted odds ratio of periodontal disease for people with diabetes was 1.22 (95% CI 1.03, 1.45) [31]. Moreover, as discussed above, in a previous US cross-sectional study, people with diabetes reported twice as many missing teeth as those without diabetes [30]. A recent meta-analysis of epidemiological studies regarding the effect of periodontitis on diabetes showed that there were significant and consistent results supporting the relationship between periodontal disease and worsening of glycaemic control in individuals without diabetes [33]. This discrepancy is likely to be due to differences in study design, population, definition for presence of periodontal disease (for example, whether ICD-10 codes or a validated probing method were used [34]), and methods for defining new-onset diabetes. Furthermore, the subjects included in our study had a higher socioeconomic status than those who were excluded. In a previous study, high socioeconomic status was associated with a low incidence of periodontal disease [35]. The difference in socioeconomic status between the subjects included and excluded in our study may explain the lower HR of the presence of periodontal disease for new-onset diabetes.

In our study, professional dental cleaning was negatively associated with the occurrence of new-onset diabetes in the univariable analysis. In a previous case−control study, professional dental cleaning was demonstrated to possibly reduce blood inflammatory biomarker levels and HbA1c [36]. The effectiveness of professional dental cleaning for glycaemic control was also demonstrated in individuals with type 2 diabetes in a small randomised controlled trial [37]. Even though our results are in line with these previous studies, the associations of dental visits for any reason and professional dental cleaning with the occurrence of new-onset diabetes were no longer statistically significant in our dataset after adjusting for various important confounding factors. These results suggest that other confounding factors are more strongly related than professional dental cleaning to the occurrence of new-onset diabetes.

In our subgroup analysis, the strength of the association of periodontal disease, number of tooth brushings and number of missing teeth with new-onset diabetes varied according to age (above and below 52 years old, the median age). Although it is difficult to give a clear reason for this relationship, we assume that genetic factors, stress, and many other general diseases may have different effects on periodontal disease, oral hygiene indicators and new-onset diabetes depending on age.

Although our study did not identify the precise mechanism underlying the relationship between number of missing teeth and new-onset diabetes, the following findings could explain this association. Poor oral hygiene may be related to the chronic inflammatory process, which affects the supporting structures of the teeth. Ulceration in periodontal pockets and teeth loss provide easy access for the translocation of oral bacteria into the systemic circulation [38], and dysbiosis of the oral biofilm with high virulence leads to indirect induction of proinflammatory cytokines [39]. The cytokines increase the inflammatory burden both locally and systemically. Moreover, inflammatory biomarkers are elevated in advanced stages of poor oral hygiene because of systemic inflammation [40]. Previous studies have reported that an increased level of inflammatory biomarkers is independently associated with insulin insensitivity and new-onset type 2 diabetes [41, 42]. Accordingly, the potentiated inflammatory reaction from poor oral hygiene may evoke impaired glycaemic control. Moreover, endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of oral bacterial cell walls, induces an innate immune reaction. A previous study showed that blood LPS levels and LPS activity were significantly increased in individuals with type 2 diabetes compared with those without type 2 diabetes [43].

Our current study has several limitations. First, our results cannot be generalised to other ethnicities because our dataset only includes subjects from the Korean population. Second, because information on oral hygiene indicators was acquired from a self-reported questionnaire, there may be recall bias. Third, the definition of the presence of periodontal disease based on the ICD-10 code using health claim data does not reflect recently published case definitions and classification criteria for periodontal disease [34]. Fourth, in our dataset, different degrees of severity of periodontal disease could not be investigated. Fifth, although our study was performed with health claim data regarding dental health check-ups, the information of detailed probing depths, attachment loss, and bleeding after probing was lacking. Sixth, because our study design was retrospective and observational, serial changes in dental health information during the study period from 2003 to 2006 were not investigated. The study design could also cause a selection bias, and therefore direct causal relationships cannot be conclusively determined. Seventh, we could not exclude all subjects with underlying diabetes because the HbA1c and oral glucose tolerance tests were not performed during health check-ups. Eighth, because our dataset came from health claim data, it was difficult to clearly distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Ninth, we could not identify the exact cause of missing teeth through health examination records. Tenth, educational level, marital status and blood inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, were not evaluated because NHIS-HEALS did not include this information. Finally, the exclusion of many subjects may have also led to selection bias.

In conclusion, frequent tooth brushing may be an attenuating factor for the risk of new-onset diabetes, and the presence of periodontal disease and increased number of missing teeth may be augmenting factors. Improving oral hygiene may be associated with a decreased risk of occurrence of new-onset diabetes.

Data availability

Inflammatory reactions are an important cause of diabetes via increasing insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction [12]. In a cross-sectional population-based sample, a positive relationship between inflammation and diabetes was demonstrated [13]. Because periodontal disease is a microbially triggered chronic inflammatory disease, associated systemic inflammatory reactions from the invasion of oral bacteria and release of inflammatory mediators could affect glycaemic control [14]. It is therefore plausible that systemic and chronic inflammatory reactions derived from periodontal disease or poor oral hygiene may impact the occurrence of new-onset diabetes [14, 15]. Furthermore, paradoxically, transient bacteraemia is also caused by regular tooth brushing, even in individuals with good oral health [16]. However, studies regarding the association of periodontal disease and oral hygiene indicators with the occurrence of new-onset diabetes are lacking, particularly in a longitudinal setting.

We hypothesised that improved oral hygiene would be associated with decreased risk of new-onset diabetes and that periodontal disease and poor oral hygiene would be related to increased risk of new-onset diabetes. The main aim of this study was to characterise the relationship between periodontal disease and new-onset diabetes. The secondary aim of this study was to identify associations of other oral hygiene indicators with new-onset diabetes in a nationwide population-based cohort dataset.

Nyhetsinfo

www red DiabetologNytt